Sample History Essay on the Whiskey Rebellion

Paradoxically, some rebellions against a democratic government can help strengthen democracy. The sample essay about the Whiskey Rebellion below provides a vivid illustration of that seemingly statement. Moreover, not only is it interesting to explore your country's past, but also clarify how a good history paper should be written in terms of content presentation and structuring. Hence, read this Whiskey Rebellion essay, learn, get inspired, and craft your own work that will awe the readers!

The Whiskey Rebellion

Taxation is one of the main ways that the government uses to generate revenue to run its programs. It is money charged on earnings, goods, and services for public use. The government utilizes the funds in activities that are aimed at ensuring that the society operates efficiently, without disruptions. Such include essential services, infrastructure development, laws and policies creation, and maintenance of social order. However, sometimes the public disagrees with such taxation measures, an example of which led to the Whiskey Rebellion.

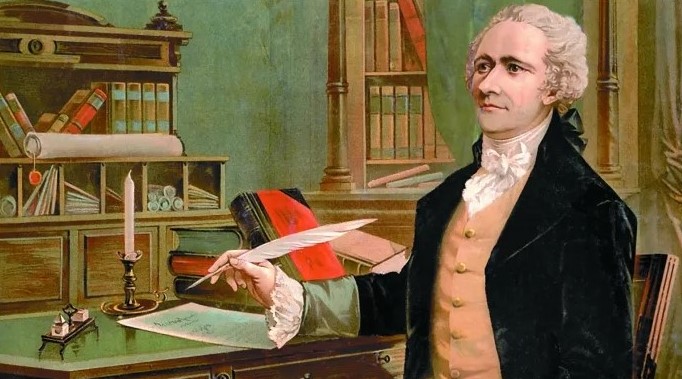

The revolt dates back to 1791 when the US Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton proposed several excise taxes as part of the financial plan to raise money to support the newly formed federal government. Among them was the controversial proposed 25% tax on all whiskey production. Particularly, the duty was aimed to settle revolutionary war debt incurred by the states, as agreed with James Madison and Thomas Jefferson in exchange for the support for the proposal to move the American capital to Washington (Ladenburg 21). The tax was approved by Congress and began to be charged.

Image 1: Alexander Hamilton, the first US Secretary of Treasury (History.com., 2020)

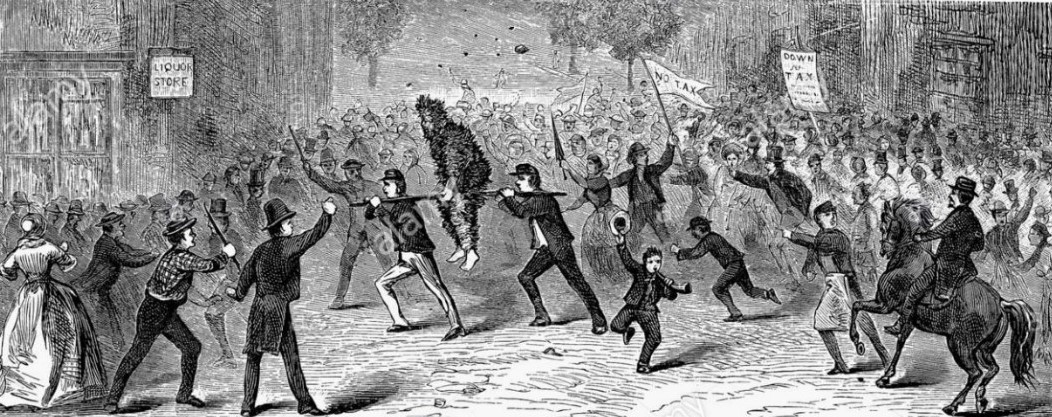

Whiskey was popular in the Western states, where it was a significant component of the region's economy. As a result, the affected areas, particularly in Pennsylvania's frontier areas, opposed it and refused to remit the dues. They held meetings to denounce the tax and collectively ascertain that they were not going to pay it. Any attempts to collect it by the tax collectors led to violence, mainly propagated by a group known as the "whiskey boys." They stripped, shaved, tarred, and feathered and tied the collectors onto poles and trees to humiliate them. The movement expanded further when the anti-federalist groups from both the Democratic and Republican divide joined, calling for the tax (Gilje 1). Committees of correspondence were formed in towns and countries and passed the resolutions not to pay the excise, with reasons. Among the primary reasons for the resistance was the perception that it was being used to punish them for refusing to buy government bonds at face value. They also saw the additional finances used to pay the bond buyers who bought them cheaply and were repaid at face value (Ladenburg 21). Therefore, the taxation was perceived as unnecessary and non-beneficial to the people paying it.

Image 2: Artistic depiction of the tarring and feathering attacks used against the tax collectors (Ladenburg, 2007)

The resistance and tactics used were also influenced by the Revolution for Independence, when Americans resisted Britain's unfair taxation. They say the whiskey taxes did not represent the citizen's interests; therefore, they were justified to fight it. Even more critically, the forceful way that the government was implementing the duty also raised the alarm about the risk of losing personal liberty to authoritarian governments, which then sparked resistance.

The government, on the other hand, was resolved to enforce and collect the tax. Hamilton was for the army to implement the new tariffs, but President Washington preferred voluntary obedience. As a result, he issued a proclamation requiring people to pay the tax and obey the law. Congress also passed a law that allowed the prosecution of those that interfered with the process (Ladenburg 21). To enforce it, Hamilton rallied the collection unit and the law enforcement to collaborate to serve the legal notices to those in deviance. For two years up to 1794, there was no significant opposition, but revolts broke out in the summer of 1794.

Image 3: Whiskey Rebellion protests at Pigeon Creek, Washington, PA (Alamy Stock Photo, 2020)

In the particular incident that triggered the rebellion, Marshal David Lennox and Supervisor of Collection John Neville moved to serve sermons to western Pennsylvania residents to appear in Philadelphia courts 300 miles away from Pittsburgh non-compliance charges. The action infuriated the people because local courts could hear them (Gilje 1). Therefore, they perceived the government as punishing them, which cemented the perception that the authorities were only interested in taxing them and not securing their wellbeing. The dissatisfaction added to the already feeling of neglect as the farmers lacked a hard currency to pay the taxes, which made the process of paying taxes hectic, even for those willing to comply.

The push by the government led people to mass action. The first incident happened in 1794 when 50 armed locals assembled at the Mingo Creek Church in Washington County and were seen joined by 5000 others that were determined to stop Marshal Lenox and Neville. On July 16, they attacked Neville's house on Bower Hill to seize the summons and his commission as a tax collector. He repelled the first attack, but they returned the next day and destroyed the house after defeating government security officers as a heavy gunfire exchange led to the death of two people. One of them was the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) veteran James McFarland who became the hero and symbol of the Whiskey Rebellion (Gilje 2). The events and Bower Hill motivated the rebels to challenge the federal government.

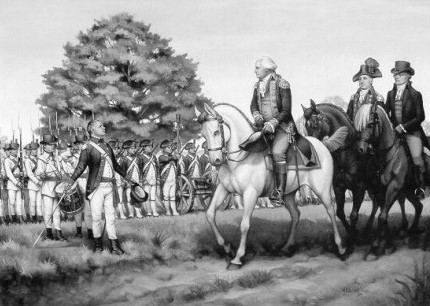

Image 4: President Washington inspecting the forces before the march to Pittsburgh to fight the rebellion (Ladenburg, 2007)

The group's substantive spokesman, David Bradford, Washington's attorney general, and seasoned Democratic-Republican politician, led the drive to occupy Pittsburg, the federal government's seat. He propagated for the formation of a militia to guide the process. He also hijacked federal mails to identify the government sympathizers among the ranks of the rebellion movement. A commission established to evaluate western Pennsylvania's situation determined that it was critical and requiring government intervention to restore law and order. On the other hand, one of the founding judges of the Supreme Court of Justice James Wilson declared the western counties of Pennsylvania in rebellion against the US government (Ladenburg 22). The proclamation legitimized any government response.

Following the determination, President George Washington ordered 13,500 troops drawn from Pennsylvania, Virginia, New Jersey, and Maryland to march to Pittsburgh to contain the insurgence. General Washington personally led the armies to Fort Cumberland, Maryland, before handing over to General Henry Lee, who marched Pittsburgh's forces. On arrival, they encountered no resistance but arrested hundreds of suspects, but no prominent figure was among them as they had freed. Most were immediately released, 20 were marched back to Philadelphia, and only two were found guilty. They were later pardoned by President Washington (Gilje 2). The operation lasted between August and November, and the trials began in December and lasted until the summer.

Image 5: Whiskey Rebellion monument in s. Main St. Washington, PA (Roadsidetoamerica.com, 2020).

The episode marked the official end of the Whiskey rebellion as no more significant actions by the group were reported. The George Washington administration used the incident to discredit the Democratic-Republican groups that lead the anti-federalist governance structure. They were depicted as disruptive and led by greed for power at the expense of peace, which reduced their authority to criticize the government. Even more critically, the federal government used the incidence to ascertain its power and legitimacy in ensuring law and order. Therefore, the Whiskey rebellion helped strengthen the newly formed government and contributed to America becoming a stable democracy it is today.

Works Cited

- Alamy. Whiskey Rebellion, 1794. / Tarring and feathering a whiskey-tax collector at Pigeon Creek, Washington County, Pennsylvania during the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Wood engraving, American, 1876. -Image ID: FFA1N7. 2020

- Gilje, Paul A. "Whiskey Rebellion." In Gilje, Paul A., and Gary B. Nash, eds. Encyclopedia of American History: Revolution and New Nation, 1761 to 1812, Revised Edition (Volume III). New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2010.

- History.com. Alexander Hamilton. 2020, Jul. 1. https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/alexander-hamilton

- Ladenburg, Thomas. The Whiskey Rebellion. Digital History, 2007. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/teachers/lesson_plans/pdfs/unit3_5.pdf

- RoadsidetoAmerica.com. Washington, Pennsylvania: Whiskey Rebellion Statue. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/52834

-

Other services: